Come Together: How the Beatles reunited to make new music in the ‘90s Part 2

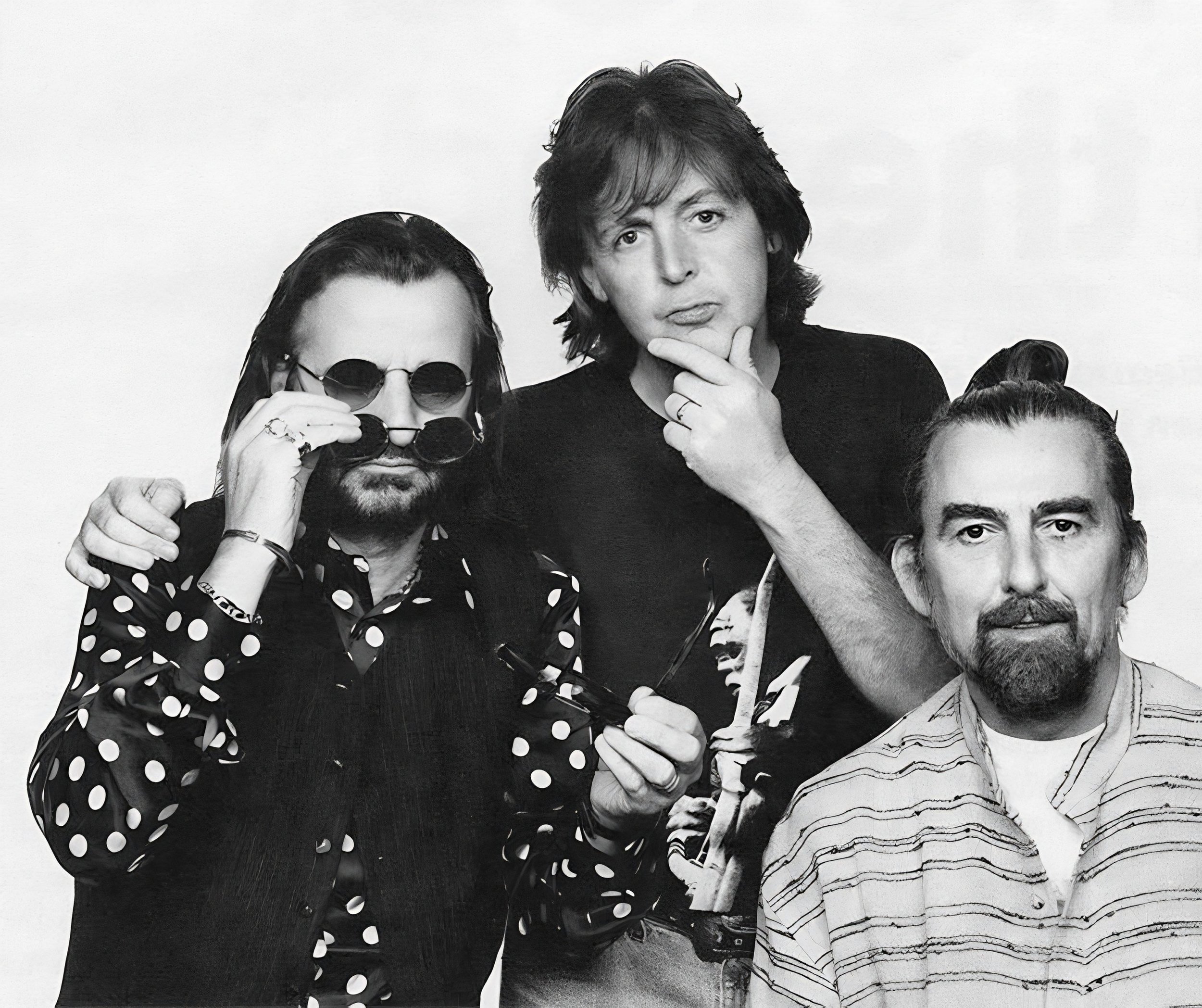

© 1995 PAUL MCCARTNEY. PHOTOGRAPHER: LINDA MCCARTNEY

Thirty years after the Beatles Anthology, it seems pre-ordained that Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr would reunite to create new music together. However, up until the very moment the trio entered the studio in 1994, it was not clear if they would make music at all or if their efforts would even see the light of day.

In Part 1 of this three-part essay, we looked at how the decision came about to make new music. Here, in Part 2, we look at how the first ‘reunion’ song – ‘Free As A Bird’ – came to be, as McCartney, Harrison, and Starr said it at the time.

Lennon’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

By McCartney’s telling, the band was set to go into the studio shortly after the end of 1993. He called Yoko Ono, Lennon’s widow, on January 1st 1994 and discussed using Lennon’s demos. Just 17 days later, on January 18th, Ono handed him a set of tapes. A few weeks thereafter, the trio entered the studio. This seems like very tight timing, and it’s likely that the timeline has an ellipsis of some sort.

Clearly, and consistent with what Harrison and McCartney both said, some discussion had taken place earlier. It’s also likely that the song selection on Ono’s part did as well given the short time period from January 1st 1994 to January 18th.

Be that as it may, after inducting Lennon into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on January 18th, Paul and Linda McCartney went back to Ono’s apartment at the Dakota in New York City. There, Ono played a series of Lennon home demos.

“She played us three songs: ‘Grow Old With Me,’ ‘Free As a Bird,’ and ‘Real Love,’” McCartney said.[16]

McCartney took an instant shine to ‘Free As A Bird.’

“I liked ‘Free As a Bird’ immediately,” McCartney said. “I just thought, shit, that is really, I would have loved to have worked with John on that. I liked the melody. It has kind of strong chords. It just really appealed to me. If John had played me those three, I would have said ‘Let’s just work on that middle one first.’”[16]

Elsewhere, McCartney said, “I fell in love with ‘Free As A Bird’”[17]

Giving veto power

McCartney understood that handing over Lennon’s demos was difficult for Ono. He knew that Sean Lennon might have reservations as well. To allay any concerns, McCartney gave them veto power over any music the group created.

“I said to [Yoko and Sean], ‘If it doesn't work out, you can veto it,’” McCartney said. “When I told George and Ringo I'd agreed to that they were going, 'What? What if we love it?’ It didn’t come to that, luckily.”[7]

While seeking Ono’s permission, McCartney did set boundaries as well. “I said to Yoko, ‘Don’t impose too many conditions on us. It's really difficult to do this, spiritually,’” McCartney said. “‘We don't know. We may hate each other after two hours in the studio and just walk out. So don’t put any conditions. It’s tough enough.’”[7]

Still, Ono’s blessing was, of course, critical. She was the protector of Lennon’s legacy. She was also his imprimatur.

“I don't think Yoko would have given [the tapes] to Paul unless she really believed John would have gone along with it,” Harrison said.[24]

Now in his late teens, Sean Lennon’s comfort was equally important. As his father often did, Sean bluntly stated the obvious.

“I checked it out with Sean, because I didn't want him to have problem with it,” McCartney said. “He said, ‘Well, it'll be weird having a dead guy on lead vocal. But give it a try.’”[7]

Carrying the weight

McCartney then took the tapes of Lennon’s demos and made copies for Harrison and Starr.[16] “It was pretty emotional,” McCartney said. “I warned Ringo to have his hanky ready when he listened to it.”[20]

Even then, it was not completely certain that the three would continue forward with the idea. It was a weighty, emotional decision.

“I mean, when I first heard John's version [of Free As A Bird], I cried,” McCartney said. “And then the idea that we were going to do it together was very, very strange 'cause we'd been meeting and chatting and doing the camera stuff, but now we were going to actually play, and you know that was a huge move for the three of us, you know, because there were four in that band and in a way we had to get over that hurdle that though John was coming out of the speaker he was not here anymore. It was a very heavy time for me.”[25]

“It was very emotional,” agreed Starr. “I mean, it was very emotional. First of all, listening to John on the tape, you know, because he is not here, but his voice was there. And then, you know, we had to, you know, we all called each other and spoke about it, you know, we had to say, ‘Okay, well, are we going to do this?’”[12]

Coming up with a solution

Indeed, while using Lennon’s demos had solved the problem of making Beatles music, it had created another one. Lennon’s voice was a constant reminder of the loss of their friend. Could they really make music together under those circumstances?

“At the beginning it was very hard,” Starr said of trying to work on a song. “It was very hard listening to the tape knowing that we were going in there to do this track with him. It was pretty emotional. He wasn’t there. I loved John.”[26]

To ease the difficulty, McCartney came up with a rather elegant contrivance. In fact, it tied back to the Beatles’ history.

“When we did Sgt. Pepper we pretended we were other people,” McCartney said. “It sometimes helps to get a little bit of a scenario going in your mind. So we pretended that John had just rung us up and said, 'I'm going on holiday in Spain. There's this one little song that I like. Finish it up for me. I trust you'…(pausing). Those were kind of the crucial words: 'I trust you.'”[23]

The idea worked.

“That’s the only way I could get through it,” Starr said. “If you asked the others I think that’s the same.”[26]

The ruse not lifted the weight of using Lennon’s demos. It also gave the three an opening.

“Once we agreed to take that attitude it gave us a lot of freedom,” McCartney said. “Because it meant that we didn't have any sacred view of John as a martyr, it was John the Beatle, John the crazy guy we remember.”[27]

The producer

When it came to determining who would produce the songs, there was some controversy. As late as mid-January 1994 – just a few weeks before McCartney, Harrison, and Starr went into the studio – George Martin seemed to be working under the assumption that he would be producing the music. He also seemed to have the impression that McCartney and Harrison were going to write songs together.

"George and Paul will have to work on material to begin with, because they are the writers, rather than Ringo. Then they'll get together, and we'll do something,” Martin said. “I know Paul and George have been talking, but I don't think they've actually written anything yet.”[28]

It also appears that, once Martin learned of the plan to work with Lennon’s home demos, he had some reservations.

“I kind of told them I wasn’t too happy with putting them together with the dead John,” Martin said. “I’ve got nothing wrong with dead John, but the idea of having dead John with live Paul and Ringo and George to form a group, it didn't appeal to me too much.”[29]

The popular notion is that Martin declined to produce the songs due to his deteriorating hearing. McCartney even reinforced this idea in some of his interviews from the time.[30] However, Martin was never asked to produce the songs.

“I think I might have done it if they asked me, but they didn’t ask me,” Martin said.[29]

At least outwardly, Martin, not surprisingly, dealt with the decision stoically. “I'm not at all unhappy about it,” Martin said. “…I knew about it, I knew it was happening, and there was no rancor about it.”[31]

Enter Jeff Lynne

There’s likely a reason George Martin thought that he would produce the new songs. Paul McCartney favored the idea.

“I was originally keen to have George do it because he'd done the rest of the Anthology,” McCartney said. “I thought it might be a bit insulting to not ask him to do this.”[17]

Harrison, however, wanted former ELO frontman Jeff Lynne. The reasoning was, at least in part, because of Martin’s hearing.

“George Harrison brought up the fact that George Martin’s hearing wasn’t as good as it was,” McCartney said. “So George Martin was okay on all the old stuff. But perhaps for new stuff it required someone who’s hearing was 100 percent. I would say, ‘Well, it doesn’t really matter: the engineer will be the ears, George will be the producer.’ But George Harrison wanted Jeff Lynne.”[7]

Lynne had previously worked with Harrison on his 1987 Cloud Nine album. Lynne was also part of the Traveling Wilburys with Harrison. The connection gave McCartney pause.

“I was worried," McCartney said. “He's such a pal of George's…To tell you the truth, I thought that he and George might create a wedge, saying, ‘We're doing it this way’ and I'd be pushed out.”[7]

For his part, Lynne said that Harrison asked him to produce the songs almost off-handedly.

“One night, we were having dinner and [Harrison] said, ‘Maybe you should do it,’” Lynne recalled. “That's what he said, and I said, ‘YES! I’ll do it.’"[32]

Elsewhere, Lynne phrased the exchange slightly differently “One day George said to me, ‘You fancy doing it, then? The Beatles one?’” Lynne said.[11]

Remarkably, in a sign of just how tightly McCartney, Harrison, and Starr were keeping information about the sessions, the news of Lynne producing did not come out until the summer of 1994, months after they recorded their first song.[33]

Deciding on the song

Having made the decision to make music together together and who would be producing, the next thing to determine was where to record. The group decided to use McCartney’s home studio out of expedience and privacy.

“We agreed to do it at my studio because this is really the only studio that was up and running,” McCartney explained. “I'd been working here regularly, so it was all cleaned and ready to go and in full working order. Also, because my studio is slightly off the beaten track – off the Beatle track! – it meant that we'd have privacy.”[34]

They did, of course, have to determine what song to work on. While McCartney was immediately taken by ‘Free As A Bird,’ Harrison apparently took some convincing.

“[George] wasn't really keen on ‘Free As a Bird,’” McCartney said. “He was saying to me: ‘I sort of felt John was going off a little bit towards the end of his writing.’ I personally found that a bit presumptuous.”[35]

In fact, Harrison preferred ‘Real Love,’ the song the group recorded for their second single. “I think George actually liked ‘Real Love’ a little better,” McCartney said.[36]

Harrison confirmed this. “When we first got the tape back from Yoko in ’93[sic], I actually preferred ‘Real Love’ as a song,” Harrison said.[37]

A bird takes flight

As they entered the studio together after a quarter century apart, there was some initial awkwardness. It quickly resolved.

“The first time the three of us got together to actually do the music was very strange,” Starr said. “We're all like, ‘Here we are.’ But, you know, 20 minutes in, it was, it was cool. We were laughing. We were having fun.”[12]

Long-time Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, who worked at the sessions, confirmed that the trio quickly hit their stride. “The old magic was there instantly, and as soon as I lifted the faders, there they were – the Beatles,” Emerick said.[38]

For ‘Free As A Bird,’ McCartney originally had a very different idea for the song than what the band ultimately went with. He imagined a grand arrangement.

“I actually originally heard it as a big orchestral '40s Gershwin thing, but it didn't turn out like that,” McCartney said. “Often your first vibe isn't always the one. You go through a few ideas and someone goes ‘bloody hell’ and it gets knocked out fairly quickly. In the end, we decided to do it very simply.”[17]

McCartney and Harrison started out playing guitars alongside ‘Free As A Bird.’ However, they immediately ran into trouble.

“First of all, George and I tried to put some acoustics on, and play along with it as it stood, because we wanted to be as faithful as possible to the original,” McCartney said. “But because he was doing a demo, John went out of time a bit.”[34]

The two tried as best they could to accommodate the tempo changes. “George and I had to keep looking at each other and giving signs through our eyes, like ‘He slows down here. He speeds up here.’ It became difficult,” McCartney said. “It became quite annoying to try and keep up with the speed changes. So it was decided that we had to take another approach.”[34]

Isolation

To deal with the tempo issues, Lynne isolated Lennon’s vocals onto a click track. The problem was solved.

“Once that had been done we were able to play with it because John was now perfectly in time, and there were just little gaps where he’d sped up or gone out a bit,” McCartney said.[34]

By the nature of the recording, they were working with a final vocal track and trying to put instruments around it. It was an unusual way to record a song to say the least.

“It’s like working backwards,” Lynne said. “Usually you start with your backing track and put your voice on it. This way you start with your voice and then put a backing track on.”[11]

McCartney subsequently played Lennon’s piano part on ‘Free As A Bird.’ This gave greater control over the song.

“John and I had very similar piano styles because we learned together – which meant that we now had a voice and a piano separate and could get control over them,” McCartney said.[34]

Making music

One of the appealing things for McCartney about ‘Free As A Bird’ was that it presented an opportunity. The lyrics were incomplete.

“The great thing about it was, [Lennon] hadn’t finished it,” McCartney said. “…So it was quite good then, because it meant okay, we’ve got to come up with something now, which was good, because now I was working with John. George and I, on the song, were actually writing with John. He hadn’t come up with the lyrics, gave us an in.”[16]

Similarly, McCartney and Harrison changed some of the chords. This was similar to how the group used to work in the studio.

“Historically what we’d say would be, ‘Hang on. I’m not sure about that chord there, why don’t we try this chord here?’” Harrison said. “So we took the liberty of doing that: of beefing the song up a bit with some different chord changes and some different arrangements, and we finished the lyrics.”[39]

Writing the new lyrics for ‘Free As A Bird’ did, however, bring some artistic tension. McCartney’s initial lyrics didn’t land well.

“George and I had a little tense moment or two on the lyrics,” McCartney admitted. “Because I’d brought in a few and he didn’t like them…He was right but it was a little tense for a moment. But we threw them back and forth and came up with something that worked.”[16]

McCartney gave a slightly different take elsewhere. “I brought in some words that I thought might do the trick, but when I went and sang them, I was having a little trouble and didn’t think they were that good,” he said. “And so, rightly enough, George and Jeff Lynne said this and then George started hacking them to pieces.”[34]

Finding compromise

At this point, McCartney had been working largely on his own for nearly a quarter century. It must have been humbling.

“I must admit, as a pride thing, that got a little difficult,” McCartney said. “I had to live with it, though, and I say now that he was absolutely right to do it and I’m glad he did it, but whilst it was going on it was a little bit hairy. It was like: here’s George savaging my lyrics, am I happy about this? And I had to keep saying, ‘Yeah, sure, sure, he’s right, he’s right, he’s right,’ and he was.”[34]

Lynne, meanwhile, had a front row seat to the lyric writing. “They just went back and forth, and it was like witnessing something amazing,” Lynne said. “I think they’d only written one song together before, and that was a long time ago…That took a couple of hours but it was a really good piece of work. And then they went in and sang them.”[11]

While writing the new lyrics had brought some tension, ultimately, McCartney said that it was nothing out the ordinary.

“Me and George, as artists, we had a little bit more tension,” McCartney said. “But I don’t think that’s a bad thing. It was only like a normal Beatle session; you’ve got to reach a compromise.”[7]

Instrumentation

For the song, McCartney used a Wal five-string bass.[31] He tried to play the song straight up.

“I didn’t want to do any of my trademark swoops or get it too melodic. I just wanted to anchor the piece,” McCartney said. “I did one or two little tricks but they’re very subtle. Like I used my five-string bass, which has got a very low string on it, and saved the low string till the tune does a big key change in the solo, and it really lifts off there. So instead of doing the same bass note I went right down to my second lowest note on the instrument.”[34]

McCartney said elsewhere of his decision to play the song simply, “I didn’t want to ‘feature.’ There are one or two moments where I break a little bit loose, but mostly I try to anchor the track.”[30]

According to Lynne, Harrison, meanwhile, played “a couple of Strats – a modern, Clapton style one (Lace Sensors) and his psychedelic Strat that's jacked up for the bottleneck stuff on 'Free As A Bird.’ They also played six string acoustics – Paul chose his Gibson jumbo while George used a smaller Martin, and Ringo played his Ludwig kit, so there are genuine Beatles drums on there.”[31]

Meet the Beatles

As Harrison and McCartney added vocals, the song started to come together. “Paul and George would strike up the backing vocals — and all of a sudden it's the Beatles again!” Lynne said.[31]

According to McCartney, Starr agreed.

“George and I did harmonies, which was finally when Ringo was chortling with glee in the control room saying, ‘It sounds like a Beatle record!’” McCartney said. “It finally did, really, sound like a Beatle record, and we were becoming more and more convinced that we were doing the right thing.”[34]

Next, Harrison started to work on his guitar parts. “He did a secondary guitar part, between a lead and a rhythm, sort of arpeggio rhythm you’d have to call it,” McCartney said. “He came up with some nice little phrases there which are very subtle on the record. I tend to hear them about the third time through.”[34]

Lynne, meanwhile, contributed backing vocals. “While [we] were working on ‘Free As A Bird,’ it came to backing harmonies, and George [Harrison] said to me, ‘Jeff is such a big Beatle fan. He'd love to get on this record. He'd just die!’ McCartney said. “…And I was a little bit reluctant. I'm a bit sort of precious, a bit private about who's in The Beatles…So we got Jeff on ‘Free As A Bird.’”[40]

Not letting it slide

Then came time for Harrison’s lead guitar parts. When Lynne suggested Harrison play slide guitar, McCartney balked.

“I was worried because it was going to be George on slide,” McCartney said. “When Jeff suggested slide guitar I thought (dubiously), Oh, it's ‘My Sweet Lord’ again. It's George's trade-mark. John might have vetoed that.”[7]

Of principal concern for McCartney was that the song sound like a Beatles track. The slide guitar had become a Harrison signature after the group broke up.

“I felt that the song shouldn’t be pulled in any way. It should stay very Beatles,” McCartney said. “It shouldn’t get to sound like me solo or George solo, or Ringo for that matter. It should sound like a Beatles song.”[34]

As a compromise, someone suggested – it’s not clear who – that Harrison play something simple and blues inspired.

“So the suggestion was made that George might play a very simple bluesy lick rather than get too melodic,” McCartney said. “And he did. What he played was almost like a Muddy Waters riff. And that really sealed the project. I thought – I still think – that George played an absolute blinder, because it’s difficult to play something very simple. You’re so exposed.”[34]

Real magic happening

True to Beatle form, the group wanted to end the song with a flourish. They decided to use ukuleles, a favorite of Harrison.

“We did the end bit, put little extra vocal things on that, and then the ukuleles, which was a tip of the hat to George Formby, whom George is particularly enamored of,” McCartney said.[34]

They also decided to use a clip of Lennon speaking. Lennon’s phrase was “Turned out nice again.”

“We got the guys at the film production office to find a clip of John talking,” McCartney said. “We gave them a certain phrase to look for, which I'm not giving away, and then we put it in backwards, just as little joke, a bit of fun that ties in with the ending.”[34]

Played backwards, however, the phrase sounded exactly like Lennon saying, “Made by John Lennon.” McCartney said that was unintentional.

“The incredible thing is, the other day, Eddie [Klein, Paul's studio manager] was working on the tape and he said, ‘Paul, listen to this’ and he played it to me and, I swear to God, the backwards stuff says, ‘Made by John Lennon.’” McCartney said. “… We could not in a million years have known what that phrase would be backwards. It's impossible. So there is real magic going on.”[34]

Accomplishing the impossible

When they were finished, all were pleased with the results. Starr said of the new track, “Sounds just like ‘em.”[26]

To Harrison, this was, of course, stating the obvious. “I mean, it's gonna sound like them if it is them,” Harrison said.[41]

They had created a construct to allow them to complete the song without Lennon. Still, thoughts of him were never far.

“I'm sure he would have really enjoyed that opportunity to be with us again,” Harrison said.[41]

For years, the group had discussed making new music but had been blocked by Lennon’s death. Now, they had managed to surmount that obstacle.

“When we'd done it, I thought, ‘We've done the impossible!’” McCartney said. “Because John's been dead and you can't bring dead people back. But somehow we did – he was in the studio.”[17]

Even Harrison, who had long dismissed the idea of a Beatles reunion, seemed pleased with the results. “It's a very happy occasion for me to hear that it actually works and to hear John's voice in the song again – that was very nice,” Harrison said.[42]

Back in the studio with John Lennon

Creating ‘Free As A Bird’ did not just mean that McCartney, Harrison, and Starr had done “the impossible” as McCartney put it. For McCartney, it also meant that he was working in the studio with his former writing partner again.

“It was the nearest I was ever going to get to writing with John again,” McCartney said of working on the first reunion song.[34]

Given the circumstances, as one can imagine, making ‘Free As A Bird’ was an unusual process for all concerned.

"It was quite spooky and emotional at first, listening to John's voice and seeing each other working again in the same room after so long, but it turned out to be wonderful,” McCartney said.[31] “Ringo had said, it might be very joyous – that’s Ringo’s word – this ancient Ringo language, it might be very joyous. And, in fact, it was quite a pleasant experience.”[16]

After finishing ‘Free As A Bird,’ McCartney wrote down his experience of making the song. It was something that he had never done before.

“The only recording session I’ve written about was the new record the Beatles made this year, ‘Free As A Bird,’” McCartney said in 1994. “…I did it just to remember the facts, really, before they were forgotten.”[27]

READ PART 3

Follow along on Facebook and Instagram.

REFERENCES (includes Part 1)

[1] Henke, James. Can Paul McCartney Get Back? Rolling Stone. June 15, 1989. Issue #554.p.42.

[2] Beatles ’95: A diary of recent news and events. The Beatles Book. No. 235, November 1995. p37.

[3] $10 Million To Beatles. Washington Post, June 4, 1986.

[4] Paul McCartney: The Rolling Stone Interview. Rolling Stone. September 11, 1986.

[5] Graff, Gary. The Wilbury’s: Almost Kin. Detroit Free Press. October 28, 1990. p.7P.

[6] Morning report. Los Angeles Times. November 29, 1989. p.F4.

[7] The Beatles, Their Only Interview! Q. Issue 111, December 1995.

[8] George Harrison interview by Frank Pangallo. Today Tonight Australian TV, November 15, 1995.

[9] Q&A with Ringo with Ringo. Beatlefan. Vol. 16, No. 5. July-August, 1995.

[10] Marsh, Dave. On the Record - George recalls the inspiration for the Beatles ‘reunion.’ TV Guide, November 18-24, 1995.

[11] Rense, Rip. Recording with the Fab Three! Producer Jeff Lynne Talks About Sessions for 'Free As a Bird.' Beatlefan, November-December 1995.

[12] Ringo Starr interview. Fresh Air by Terri Gross. NPR. June 14, 1995.

[13] Sharp, Ken. Ringo Talks! The Beatles Book. No. 231 July 1995. p.33.

[14] Beatlenews Roundup. Beatlefan. Issue #86. Vol. 15, No. 2. 1994. p4.

[15] George just loves it here. Sunday Mail (Adelaide). November 7, 1993. p.E.

[16] Kozinn, Allan. McCartney on the 'Anthology' - The Inside Story on the Film, Album and Reunion. Beatlefan. Issue #97. Vol. 17, No. 1. November-December, 1995.

[17] Snow, Mat. Paul McCartney. Mojo. November 1995.

[18] Forward Into the Past. Rolling Stone. February 10, 1994.

[19] Norman, Philip. Why John was wrong to block a Beatles reunion. Daily Mail. November 13, 1995.

[20] Bradshaw, Nick. How a sad song made it better. Sunday Express. October 29, 1995. p122-123.

[21] Anthology Electronic Press Kit. November 7, 1995.

[22] Yoko Ono stays in background but gives blessing to Beatles reunion. The Atlanta Journal. November 19, 1995. pL9.

[23] Giles, Jeff. Come Together. Newsweek. October 22, 1995.

[24] Wigg, David. Fifth Beatle takes a last bow. Daily Express. November 24, 1995. p.43.

[25] Meet the Threetles. Beatlefan. Issue #104. Vol. 18, No. 2. January-February 1997. p.13.

[26] Sharp, Ken. Beatles “cool” says Ringo. Record Collector. July 1995, No. 191.

[27] The Club Sandwich McCartney Interview. Club Sandwich. Winter 1994, No. 72.

[28] Wigg, David. Rebirth of the Beatles. Daily Express. January 22, 1994. p.21.

[29] Sharp, Ken. The last hurrah of the fifth Beatle. Goldmine. Vol.24, No. 23. Issue #477. November 6, 1998. p.18

[30] Paul McCartney interview. Bass Player. July/August 1995.

[31] Cunningham, Mark. The story of the Beatles Anthology project. Sound On Sound. December 1995.

[32] Jeff Lynne Interview. Good Day Sunshine. Issue #79. Winter 1995

[33] New Beatles record, anyone? Mojo. July 1994. p.14.

[34] Baker, Geoff and Lewisohn, Mark. The Beatles Story. Club Sandwich. No. 76. Winter 1995.

[35] Giles, Jeff. The World According to Paul. The Times Magazine. November 11, 1995.

[36] Badman, Keith. The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After The Break-Up 1970-2001 (p. 1302). Omnibus Press. Kindle Edition.

[37] White, Timothy. Magical history tour: Harrison previews ‘Anthology Volume 2. Billboard, March, 9 1996.

[38] Stapley, Patrick. The Beatles: Yesterday and today (and tomorrow). EQ. November 1995.

[39] George Harrison interview. Q. Issue #111. December 1995. p.124.

[40] Meet The Beatle. Q Magazine. June 1997. #129.

[41] George Harrison talks about the Beatles Anthology. 2 minutes 21 seconds.

[42] Kelson, Paul and Raynor, Paul. Another bite of the Apple. . . and what do others think? The Guardian. November 21, 1995.